This week marks the end of two new months, one year and one decade, with Kislev making way for Tevet, December for January and good ol’ 2019 for 2020, launching a new decade in the process. This is always a good time to contemplate the situation – what last year was like, and what type of exciting things the new year holds. So this week I shall resume our discourse on variety, diversity and their each individual importance (other than the beauty of it all).

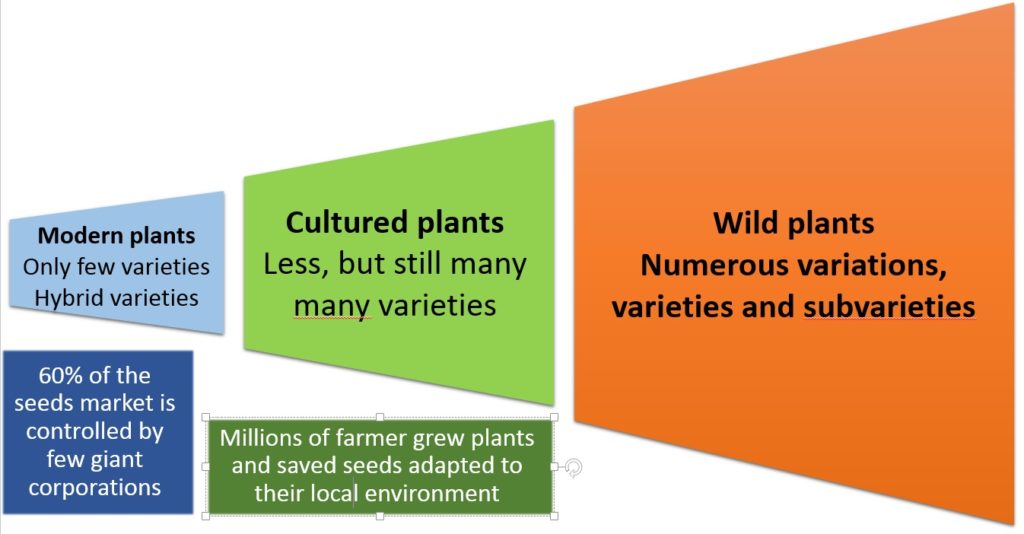

In our previous newsletter, we looked at the development of agriculture and the cultivation of various plants over the globe, till reaching the pastoral state of millions of farmers tending to their small plots to grow species which, over time, developed into crops customized to local soil, climate and pests. In the process, thousands and tens of thousands of sub-species of plants were created for food and other uses. Unfortunately, this is no longer the situation…

A major part of this alteration is related to “The Green Revolution,” a process that occurred between 1940-1960, specifically in Mexico and India. This revolution included growing new species, using chemical and machine-controlled fertilization and pesticides, and developing monoculture (the agricultural practice of producing or growing a single crop, plant, or livestock species, variety, or breed in a field or farming system at a time). The project emerged when Mexico turned to the U.S. for help in the face of looming mass hunger resulting from a major population expansion (and the slowing down of food production). Together with the Rockefeller Foundation, they developed a practical research center aimed to accelerate wheat production in Mexico. Headed by American agronomist Norman Borlaug, the researchers succeeded to develop new wheat species that produced double the yield, were easy to mechanically cultivate, and maintained resistance to diseases and pests. After the Mexican success, these methods were adopted by India where elite species of rice were developed. Norman Borlaug was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work.

Green Revolution researchers and farmers had good intentions, and the crops they developed were indeed “elite species.” But in their wake, the byproducts of this accelerated pace and expansion of food production quantities were the widespread use of chemical pesticides, vigorous growth which diminished the soil’s fertility, and, circling back to us, a decline in the variety of seeds. For example, thousands of wheat, rice or corn species that had grown over the world prior to the Green Revolution were reduced to several dozen elite hybrid species grown industrially worldwide. These new hybrids could not be kept from one year to another (hybrid species do not yield identical offspring), thus control over distribution and production of seeds was completely altered. From millions of farmers individually saving good seeds from one year to another, the global seed market is now controlled by several generals.

Israeli wheat is a prime local example: wheat was probably cultivated in this area some 10,000-12,000 years ago. A century ago, Aaron Aaronsohn discovered the wild wheat near the northern settlement of Rosh Pina, and over the years traditional wheat was consistently grown. Customized to the soil and specific micro-climates, thousands of traditional species developed in villages of the area with no notable differences in characteristics, etc. The local species consisted mainly of Durum wheat – hard wheat from which pitta bread and pasta are produced. The Zionist pioneers who came from Europe in the 20th century changed the picture…. They, who came to Israel to “build and be built” and create the “New Jew,” still found it hard to give up the food they were accustomed to, and the local wheat just didn’t produce their beloved European-style loaves of bread. Thus, the seeds of bread wheat they imported to Israel eventually took over the majority of the local yield, with most of the traditional types being lost in the process.

Luckily, there were agronomists who insisted on keeping the traditional species, believing that even if not all species are grown industrially, it is important to preserve them. Over the years, wheat and other seeds were gathered from across the country, both cultured and wild species, and kept in research labs. An equivalent process took place (and still exists) in the world, where seeds are gathered from wild plants and traditional culturized yields to be stored in seed banks at deep freeze (-18°), stringently dry conditions. The world’s most famous seed bank is on an isolated island north of Norway, hewn in an iceberg with approximately one million seed swatches from across the globe. Take a look:

But other than the need for nostalgia and blasts from the pasts, what is the importance of keeping millions of species, some of which are not even industrially grown? Why put so much energy and effort into collecting and preserving them? Shouldn’t we just let bygones be bygones and move on to 2020?

The answers are – of course – varied, but truth be told, the need is all the more powerful in 2020.

Medical scientific research is largely based on botanica. Much of the medicine we know today is a product of plant material, thus the genetic decrease of plants also diminishes the chance to find the next plant-based medicine. Frequently the active component exists in larger quantities and potency in wild plants, and less within the hybrid and/or cultivated plants. A wide variety of plant species allows the continuation of researching and utilizing the non-edible virtues of plants.

Unfortunately, the modern era has been riddled with natural disasters (tsunamis, earthquakes, forest fires) and man-made wars. The result is always serious damages to plants and fields. In the Malaysian and Indonesian tsunamis, rice fields were severely injured, resulting in the loss of traditional, locally-acclimated species. The seed banks came to save the day: seeds that had been kept for emergencies were removed to be reseeded the damaged fields. Warfare in Iraq and Syria also caused harm to the variety of seeds, in this case due to looting and vandalism of the local seed banks. The Syrian War caused the demise of the important Icarda seed bank, an organization that researches and works to preserve agriculture in countries across the non-tropical dry areas. Eventually, this seed bank was moved to Morocco and Lebanon, after being replenished from various seed banks worldwide where Icarda collections were preserved.

Plant epidemics, too, are a serious danger in the era of monoculture unvaried planting. The great famine in 19th-century Ireland damaged most of the Irish potatoes, already scarce species, causing massive starvation. Then there is the Panama Disease that damaged banana roots, nearly eliminating the banana industry after the major specie was badly injured. And today, wheat is being threatened by a violent strain of Puccinia.

Lastly, the climate changes hovering up the road will be accompanied by high temperatures, low precipitation and new species of pests. In order to confront these changes, plants will need to acclimate, develop tolerability and an ability to withstand ever more difficult conditions. The solution to these epidemics and climate changes lies in genetic research dedicated to locating the resilient characteristics (to those diseases), and thus attain the ability to create hybrids of new, vigorous species. And for that we need… you guessed it, genetic variety that exists in traditional and wild plants.

In order to create a new species, the developers choose wild and traditional species with adaptive, resilient characteristics, and create new species from them. This type of development can take between seven to 10 years. We wish them good luck and anxiously await the final product!

Wishing you a week of continuing light, and a 2020 full of great surprises, variety and abundance, respect for the past and hope for the future!

Alon, Bat Ami, Dror, Orin, Yochai and the Chubeza team

____________________________________________________

WHAT’S IN THIS WEEK’S BOXES?

Monday: Swiss chard/totsoi/kale, kohlrabi/fennel, fresh onions, cucumbers, tomatoes, broccoli/cabbage/cauliflower, carrots, parsley/coriander/dill, lettuce, daikon/baby radishes. Small boxes only: peas/Jerusalem artichoke. Special gift for all: mizuna/ arugula

Large box, in addition: Celery/celeriac, beets, scallions/New Zealand spinach, turnips.

FRUIT BOXES: Bananas, oranges, pomelit, avocadoes.

Wednesday: Swiss chard/totsoi/kale, kohlrabi/fennel, fresh onions, cucumbers, tomatoes, broccoli/cabbage/cauliflower, carrots, parsley/dill, lettuce, peas/Jerusalem artichoke, celery/celeriac. Special gift for all: mizuna/ arugula

Large box, in addition: Beets, scallions/New Zealand spinach, daikon/baby radishes/turnips.

FRUIT BOXES: Bananas/avocados, oranges, pomelit/clemantinot, granny smith apples.