New from the Ein Harod fields – Organic Teff Flour (in 1kg or 500gr)

For some years now, we’ve joined forces with the Ein Harod (meuchad) fields – one of the pioneer and very successful organic fields in the country. Kibbutz Ein Harod is located in the Jezreel Valley, where for over 98 years (!) they have been cultivating the very fertile soil of the region. For almost two decades, a large part of the field has been organic, growing wheat, hummus, teff and more, in addition to almond and olive orchards. Alongside the flourishing, blooming fields, the classic Ein Harod apiary has been cultivating bees for the past 95 years, producing pure honey, unheated, with no added sugar.

For some years now, we’ve joined forces with the Ein Harod (meuchad) fields – one of the pioneer and very successful organic fields in the country. Kibbutz Ein Harod is located in the Jezreel Valley, where for over 98 years (!) they have been cultivating the very fertile soil of the region. For almost two decades, a large part of the field has been organic, growing wheat, hummus, teff and more, in addition to almond and olive orchards. Alongside the flourishing, blooming fields, the classic Ein Harod apiary has been cultivating bees for the past 95 years, producing pure honey, unheated, with no added sugar.

Order today from the wonderful array of Ein Harod field and apiary products, including organic olive oil, organic hummus, natural honey, organic teff seeds, and finally the new kid in town – organic teff flour! (The almond crop is finished for this season, before making its return debut in the fall.)

I highly recommend this gentle, tasty and healthy greeting from the beautiful Yizrael Valley.

___________________________________________

And it’s back! The Seventh Chalk Art Festival, today, Wednesday, May 22, from 10:00am-6:00pm

And it’s back! The Seventh Chalk Art Festival, today, Wednesday, May 22, from 10:00am-6:00pm

A full day of art, games, stories and everything that involves chalk. A day of wondrous meets with street artists in music and art; a day of mutual adult/children drawing – regardless of your level of artistic talents.

A day of discovery, learning, cooperation, initiation, creativity, encouragement, self-acceptance and more. Come soon!

______________________________________

The Hum of the Bees

Today Michael came by, the Bumblebee man from Kibbutz Yad Mordechai, and together we distributed beehives throughout the tunnels and our tomato hothouses. So I’m taking the opportunity now to fill you in on the behind-the-scenes pollination we do in our growth houses with the assistance of bumblebees – in perfect timing for our new growth houses and the arrival of spring (hoping the heatwaves pass…).

When we grow a plant in the open field, we allow nature to take things into its own hands. Mainly this involves maintaining a balance between the destructive and the beneficial insects (who devour the bad guys). In addition, pollinating and fertilizing the plants – completing the process from flower to fruit, is carried out naturally and simply by wind or the many insects flying around humming in the open spaces of our vegetable beds. Simple, right? Even perfect!

However…. sometimes the insect damages are so severe that nature can no longer cope. The balance is drastically disrupted almost to the point of no return in the open field. Take the tomato, for instance. In the open field it is attacked by various viruses (Tomato yellow leaf curl virus, for one) spread by the silverleaf whitefly and the California thrip. Also, the Tuta Absoluta moth (such a cute name for such an annoying pest) can really injure the tomato, not to mention the threats of various Acaris. In short, we have lots of tomato-loving partners, which is why after many years of growing them in the open field, we decided to move them to a closed space, covered by a dense mesh net to protect the vulnerable tomatoes from their enemies.

But in order for the nice tomato flower to turn into the reddish fruit we so love, pollinating is required – i.e., transferring pollen from the stamen to its female reproduction parts (its “ovaries”). The tomato flower loves the number six: it has six yellow petals and six stamens producing the “stamen poll” surrounding the style which usually hides within it (though sometimes the style is taller than the cone and peers out from inside) at the edge of the stamens there are small openings to set free the tiny pollen seeds.

The tomato flower belongs to a small group (approximately 8% of flowering plants) that are pollinated by “buzz pollination” in which the tiny dry pollen grains roll out of the cone stamen openings as a result of the flower being shaken (by wind or insects). Every shake distributes a small part of the pollen – similar to shaking salt over a salad. The pollen pours into the stamen cone and lands on the stigma situated at the top of style. The flower is usually open for three days and the pollen begins venturing out approximately 24 hours after opening up, thus the flower has a two-day window of opportunity to “find its one and only buzz,” be fertilized and turn into fruit.

And this is where the bumblebee enters the picture. Israel is home to three bee family (Apidae) members. They reside in the cool mountains up north, in the Hermon, Galilee and Carmel. The most common species in Israel, the buff-tailed bumblebee, is widely prevalent throughout Europe and Asia and probably arrived here from Lebanon. The head of the buff-tailed bumblebee is relatively small and its body is covered in black hair and two brown-yellow strips. The back of its belly is covered with white hair. This is the main specie, domesticated worldwide which since the 90’s has been used as an “agricultural assistant” pollinating plants that grow in closed spaces. Take a peek at the charming lady:

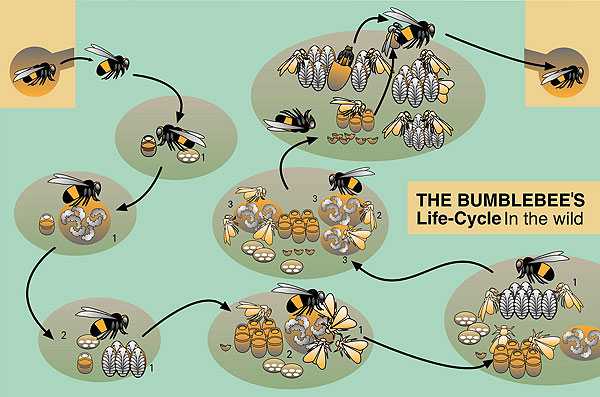

Like their cousin the honeybee, buff-tailed bumblebees are social creatures. As such, they live in a colony governed by a very strict work distribution among the bees who are in charge of reproduction – the males and queens – and the plebes – the worker bees. However, in contrast to the honeybees, they are rather primitive: their colonies – the social aspect of their lives – only exist throughout springtime and summer when flowers bloom. In wintertime only the queens exist, and they are basically inactive, spending their winter slumbering in hidden places. The queen – who was coupled and fertilized before falling asleep – awakens in springtime and begins collecting nectar and pollens, searching for a suitable place to set up her nest. She then lays eggs, collects food, heats and feeds the bee larvae that hatched until they pupate, and then resumes her egg-laying. Life in the colony begins when the first worker bees hatch from the pupae. The workers go out to collect food and take care of the newborns, allowing the queen to get some rest and continue to lay eggs. The colony now grows rapidly – capable of hosting hundreds of bees, most of which will be workers who set out to graze the flowers, collect food and consequently pollinate them. At the end of summer or towards autumn, the final bee baby boom arrives, this time born of the reproducing species (queens and males). The remaining workers die together with the old queen, while the young queens mate and begin hoarding a mass of fat in preparation for winter slumber. Colony life thus reaches its termination.

At the end of the 1980’s, Europe achieved full domestication of the bumblebees, allowing them to grow under artificial conditions throughout the year, not only in spring and summer. This development was the key to using bumblebees for agricultural pollination in growth centers, and within four years they replaced manual pollination in tomato houses throughout the entire Western world.

When a worker bumblebee sets out to graze the fields and meets a tomato flower, it is able to shake it using its natural expertise – buzz pollination (unlike its cousin the honeybee which cannot shake). She is quite an efficient worker: a large amount of pollen is caught by her hair, and her rapid movement amongst the plants allows for a great deal of pollination. She is also active in cold temperatures and cloudy, rainy climates (remember – she originated in Europe), and does not suffer from claustrophobia: closed places in hothouses and tunnels do not bother her, nor do filtering sheets spread above mar her sense of direction. Take a look at this beautiful demonstration of the bumblebee doing her thing.

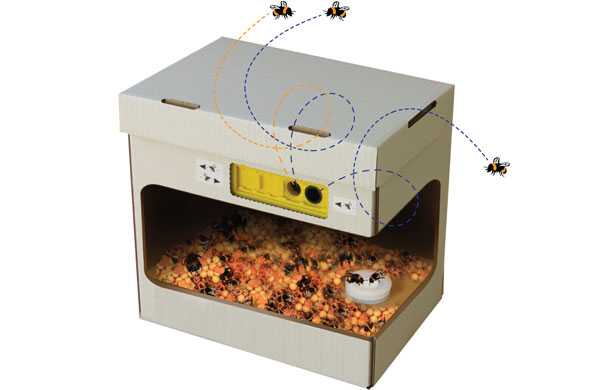

When we introduce a new beehive to our growth house, we do so by hanging a plastic box on the trellising (to prevent ants), and place the new hive within it. In the female-dominated hive, there is one queen, pupae, newborn larvae and eggs. In addition, dozens of worker bumblebees fly around buzzing loudly, waiting for us to open the small opening in the hive and allow them to exit and begin skipping and hopping amongst the flowers. In warm springtime or summer, we make sure to hang the hive as low as possible and among the rows of plants (which shade it) and place insulating styrofoam on its roof to ease the burden of heat for our European friends. The tomato flowers do not produce nectar which the bees exist on, thus the hives come fully-accessorized with a nectar substitute (usually sugar water) in a quantity set to last for the entire season of pollinating activity. This is how it looks from within.

Amazing and beautiful, don’t you think?

We will part with a fervent thank you to the very diligent bumblebees, in appreciation of their ceaseless movement, unrelenting work, persistence and the calming hum always in the background.

Wishing you a buzzing week, swarming with activity, growth, budding, pollination and community,

Alon, Bat Ami, Dror, Yochai and the entire Chubeza team

_____________________________________________________

WHAT’S IN THIS WEEK’S BOXES?

Monday: Zucchini, beets, lettuce, carrots, cucumbers, tomatoes, potatoes, onions/garlic, cabbage, kale/New Zealand spinach/ Swiss chard, coriander/dill/ parsley

Large box, in addition: Fakus /cherry tomatoes, leeks, parsley root

FRUIT BOXES: Apples, bananas, nectarines, melon

Wednesday: Zucchini, beets, lettuce, carrots, cucumbers, tomatoes, potatoes, onions/garlic, kale/New Zealand spinach/ Swiss chard, coriander/dill/ parsley, cherry tomatoes.

Large box, in addition: Fakus/butternut squash, cabbage, leeks/parsley root

FRUIT BOXES: Apples, bananas, peaches, melon.