We are delighted to inform you that the Matsesa has launched a limited edition of wintery warm cider with 5.5% alcohol. Choose from three deluxe favors:

- Apple cider with rosemary, star anise and lavender

- Apple cider with cinnamon, clove and star anise

- Pear cider with sage, rose petals and cardamom

Best sipped hot, but also delectable as a cold drink with ice.

You are welcome to add this gourmet delight to your veggie box via our order system and savor every drop…

___________________________________ Come take a peek at our garden Parliament of all that grows The beds so green Our joyful hearts ardent Each vegetable raises its head with a flair And the sweet flower fragrance fills all the air

Moshe Aharon Avigal, from: Kulanu Hever Poalim, anthem of the first School for Workers’ Children in Tel Aviv (loosely translated by A. Raz-Meltzer)

We do tell you that we grow vegetables in the Chubeza fields. But unlike fruit, where you’re pretty sure what you’re supposed to eat (the part that includes seeds, surrounded by juicy and fleshy matter, and wrapped in a peeling), vegetables are far more confusing since we call almost all edible parts of a plant “vegetables,” sometimes even when they are fruit… I could say that in general, the edible parts are green and fresh, but we refer even to the dry parts (e.g., garlic or onion) as vegetables.

So, this week we shall explore some of the vegetables from this angle: what part of the plant is actually in your box this week?

Let’s start with a short quiz: What plant part is each of the following vegetables:

If you gave a different answer to each picture, you may actually be right. In Chubeza’s winter vegetable boxes we are able to enjoy all parts of the plants, from head to toe or rather from root to fruit. There are roots, stems, leaves, flowers, fruit and pods. Some I’m sure you can easily recognize, but others are more surprising. Time to embark upon our fieldtrip:

The root of the matter: Usually plants develop their roots underground where they are used to grasp onto the soil and soak up water and nutrients. There are also roots which store food, ventilate or reproduce. The edible roots are almost always storage roots, chockfull of the nutrients that the plants stored within them. Our boxes contain such roots as: Tubers (the thickened underground part of a stem), either sweet like the carrot, beet and sweet potato, sharp like the radishes and daikon, or mildly sweet like the turnip, celeriac or parsnip; Bulbs (the part of the stem that functions as a food storage organ and has thus thickened and lost its chlorophyll) such as the Jerusalem artichoke; as well as onions composed of layers of scales (a modified type of leaf that changes in order to act as a storage organ and has lost its chlorophyll): onion, fennel and garlic. As mentioned, the roots do not include chlorophyll, the substance responsible for the green color in most parts of the plant. In the absence of chlorophyll, our roots transform into a range of lovely hues: orange, purple, yellow, pink, and white… When we pick roots, we are in fact pulling them out of the soil, sometimes assisted by a pitchfork, while other times (though not always), we cut off the part above the roots: stems and leaves. Once picked, the roots that dwelt in the wet wintery soil are usually in need of a nice soak in the tub before being packed up and delivered to you.

* Perhaps you’re thinking: but wait, what about the potato? Well, Mr. Potato does not belong here because he is not a root! But we’re jumping ahead of ourselves. Patience!

From the root, we ascend to the stem: The stem is the organ that sprouts up from the root, and most leaves sprout from it. The stem’s main job is to transport food from the roots to the rest of the plant parts via its transportation pipes. The root’s secondary role is to uphold the rest of the plant parts, something like a green spine. Our boxes include stems that are also connected to their roots, like the scallion, or stems without leaves, like the celery. Winter-thickened stems are treated respectfully at Chubeza – these are the vegetables who at first glance look like a bulb or onion and are easy to confuse, but they are in fact a thickening of the bottom part of the stem, just above the topsoil. Did you guess it right? Yes, I am referring to the kohlrabi and fennel. Unlike roots, these two are not tugged out of the soil but rather released by being cut away from the strong root connecting them to the earth. If you look closely at the bottom of a fennel or kohlrabi, you can see the actual slicing mark.

Now, it’s time to guess the identity of another distinguished thickened stem which frequents your boxes quite often: It’s hard to realize that this vegetable is a stem, because unlike “regular” stems, this one is an underground thickened stem. The telltale factor is that it did not lose the ability to produce chlorophyll. Though it doesn’t develop within the vegetable as long as it lies dormant in the dark earth, when exposed to the sun it takes on a greenish hue. Have you figured it out yet? Of course, this is the potato! The potato bulbs develop from underground thickened stems, and as mentioned, the potato’s greenish hue is a sign that chlorophyll is developing upon being exposed to the light, because after all, it is still a stem…

Keep on climbing, and we reach the leaves: Leaves are in fact the mouth of the plant, which it uses to “eat” light and thus create energy via photosynthesis. Leaves usually sport a shade of green (but not always) due to the chlorophyll, that same pigment which helps to carry out the photosynthesis, and water+CO2+light result in sugar, i.e., energy. Chlorophyll (from Greek: khloros: pale green; phyllon: leaf) could be translated ‘the green of the leaves.’ The smooth leaf which connects the leaf to the stem is termed ‘petiole,’ while the body of the leaf is the ‘lamina.’ Within the lamina are veins whose job is to transport nutrients to the leaf: In the center you can identify the Midvein that splits sideways into smaller (secondary) veins. There are many leaves in your winter boxes, in various shapes and uses. The small or tiny leaves of the parsley, dill and coriander are used for seasoning. Slightly larger leaves like tatsoi, bok choi, mizuna, arugula or lettuce are usually designated for salads, and huge leaves that can sometimes cover the entire length of the box and more, like Swiss chard, kale and spinach, are generally cooked. But there is one more serious leaf vegetable in your box that may look a little different because its leaves are not flat: the cabbage. At a certain point in its growth process, the leaves begin to grow inwards creating a ball-shape, with more and more leaves growing inside this ball and compressed within to create the cabbage head.

-

- חסה ערבית – עליה מוארכים ובשרניים במרכזם. Romaine lettuce. Its leaves are elongated and fleshy in the center.

-

- חסה מסולסלת ירוקה/סגולה: מוצאה מאיטליה ועליה המסולסלים ירוקים בחלקם התחתון וסגולים בקצוות. Green or red leaf lettuce: originally from Italy, its curly leaves are green on the bottom and purple at the edges.

The next stage in the plant’s development, after it sprouts a stem and leaves above and sends its roots deep down under, is the blossoming. The flowers are the plants’ reproductive organs – they create the reproductive tissues (the male Stamen and the female Pistil), and summon the rendezvous between the reproductive tissues within the flower or other flowers. Ultimately, they are the substrate on which the seeds are created, allowing the continuity of the plant world by disbursing its offspring and expanding the area of its growth. The Pedicel connects the flower to its stem, while at the base of the flower is the Receptacle upon which the organs of the flower are arranged. When there are an abundance of tiny flowers crowding together on a receptacle, we call it a flower head (or pseudanthium).

Your winter boxes host two beloved flower heads: the cauliflower (as evident in its name in many languages) and broccoli (that resembled an arm or branch to the name givers, who granted them the less illustrious title). We eat them when the flower is closed, before it has developed and opened up, but if you allow the broccoli or cauliflower to continue growing, they will develop the very many small flowers grouped together in the head and a beautiful bouquet of Cruciferae flowers will grow from the center.

The next stage of the growth is fruit. To be honest, if we only ate vegetables in season, winter would not be the time to discuss vegetables that are fruit, as winter is slow and growing takes time and progresses slowly. Fruit – the highlight of the plant – arrives at the end of its growth. After the stems and leaves grew, a flower developed and fertilization occurred, and the seeds developed and matured, a juicy, nutritious material often develops around them wrapped in a peeling. Most of these vegetable delights are berries (moist and juicy flesh; containing more than one seed with a thin, flexible outer layer) and they grow in the summer: eggplant, pepper, squash and pumpkins, melons, watermelon, fakkus, zucchini and others. Which is why they do not come to visit during this time of the year (we said our final goodbye to the pumpkin this week). But two of them actually grow here year-round and enjoy a growth spurt in wintertime thanks to our growth houses: the cucumber and tomato, the royal couple of the Israeli vegetable salad (but now we know that it is in fact a fruit salad…).

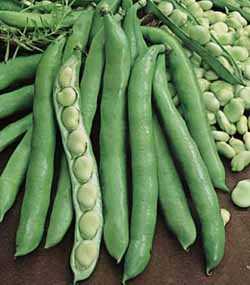

Aside from the juicy, fruity vegetables, there is one very special family in our field whose offspring are also fruit, but of a different kind. The legume pods boast distinguished representatives in springtime, summer and autumn: green beans, black-eyed peas and edamame. But they are well-represented in wintertime as well with peas and fava beans. The green legume pods are a very unique vegetable-fruit because they lack juicy flesh surrounding the seeds, but sport instead an elongated pod in which the large seeds are laid out Indian-file.

The great variety of the wintery vegetable garden and your boxes is a stark reminder of nature’s wise diversity: the plant parts are versatile, as are the various stages of development, different strengths, varied colors, shapes and characteristics. The content of your boxes must always be different, varied and pluralistic in order to be plenty, to allow life and be sustainable.

May we learn more from nature in 2021: how to embrace difference, variety, and multiplicity, and how to grow along with them.

Wishing you a good week in which we will bid farewell to this strange and confusing year. Let’s hope for a new year that is just a little more boring….

Alon, Bat-Ami, Dror and the Chubeza team

___________________________________

WHAT’S IN THIS WEEK’S BOXES?

(Quiz yourself! Which part of the plant is each vegetable in your box?)

Monday: Swiss chard/kale/mizuna, lettuce, daikon/baby radishes, broccoli/cauliflower, cucumbers, tomatoes, turnips/beets/kohlrabi, Jerusalem artichokes/peas/cabbage/fennel, coriander/parsley/dill, carrots, sweet potatoes.

Large box, in addition: Celeriac/celery, onions or a bundle of new onions, spinach/totsoi/arugula.

FRUIT BOXES: Avocado, clementinas, red or green apples/kiwi, pomelit/pomela/ oranges, bananas.

Wednesday: Swiss chard/kale/New Zealand spinach, lettuce, daikon/baby radishes/kohlrabi, broccoli, cabbage/cauliflower, cucumbers, tomatoes, turnips/beets/fennel, coriander/parsley/dill, carrots, sweet potatoes/potatoes/a bundle of new onions .

Large box, in addition: Jerusalem artichokes/peas, Celeriac/celery, winter spinach/totsoi/mizuna/arugula.

FRUIT BOXES: Avocado, clementinas, red or green apples/kiwi, pomelit/pomela/oranges, bananas/lemons.