Changes in Schedule over Pesach: No deliveries will take place over Chol Hamoed (Wednesday, March 31 and Monday, April 5.) Therefore:

* Monday deliveries will take place on Sunday, March 28th, and then Monday, April 12th

* Wednesday deliveries will take place on Wednesday, March 24th, and on Wednesday, April 7th.

Bi-weekly recipients: note that in the absence of Pesach deliveries, you will actually skip three weeks of delivery. If you wish to bring up your delivery dates, please advise ASAP.

If you wish to enlarge your box for the holiday, please advise ASAP!

Open Day: In the Chubeza tradition, we cordially invite you to one of the two annual pilgrimages to our field. This year’s festivities will take place on Thursday, April 1st (7 of Nissan), between 1:00 PM – 6:00 PM. Open Day at Chubeza gives us an opportunity to meet, tour the field, nosh on vegetables and cook delicacies. Children have tailor-made tours, suitable for small legs and curious minds, creative activities, and a great open space to run free.

_____________________________________________

The Strange Disappearance of Mr. Fava Bean

We had fervently hoped to add (for those who requested) nice festive fava beans in your pre-Pesach boxes to adorn the holiday table, but, alas–perhaps due to the excitement of the holiday– our fava bean bade us farewell last week. And perhaps there is something that makes him flee every year just before Pesach: if my memory serves me well, over the past four years we’ve always lacked nice fava beans at this time of the year. And I guess we can understand Mr. Fava’s bewilderment: there are some Pesach tables where he is a most welcome guest, while at others he is cast away to the chametz cabinet along with his fellow legume brethren. Either way, this year the reasons for the fava’s premature departure were the powerful rains and then the heat wave that destroyed the many flowers that filled the strong plants, preventing other pods to grow and ripen. Sadly, those second and third rounds of fava that we’d depended on harvesting are prematurely deceased, and I apologize to all who awaited them. We are as disappointed as you…

In honor of the fava bean, Pesach, the seeding of the first black-eyed peas (lubia) and sweet corn last week, and to mark the upcoming Open Day where we will be using various seeds collected at Chubeza to make arts and crafts projects, I decided to bring back a previous newsletter devoted to grains and legumes.

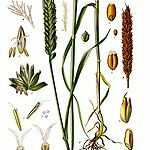

We’ve already discussed the multiple Pesach-personality of the fava bean, so let’s dedicate some words to the general major confusion in the grains and legume world of chametz. The Grain Family is a fundamental botanical family, the Poaceae family, or the Gramineae. It is one of the most important plant families to economics and human culture, essential to daily food consumption by humans (grains constitute almost every slice of bread) and animals (as fodder and pasture), as a main source of sugar (sugarcane and corn), as building material (bamboo in Asia) and of course, as natural ornaments (lawns and more). It is a relatively young family (55-65 million years old), characterized by grass with hollow stems (canes) usually in a node formation, which provides them with stability and the ability to bend without breaking. As they are fertilized by the wind, grains have no need for any colorful prissy flower to attract pollinators; their flowers are characteristically green-brown-yellow, as the color of the plant itself. The grains are usually organized in spikes.

The seeds of the Graminaes are usually monocotyledon (meaning, they have one kernel sperm. This is demonstrated by the fact that their seed does not split in half. Think about the corn or rice kernel, as compared to fava or pea seed.) Almost all of them are edible, but many varieties are so small that they’re not widely grown commercially. Another characteristic of the grain, which is problematic in farming, is that most spread their seeds by bursting the spike and whirling their kernels to the wind, which becomes a problem for those who wish to reap or gather them. Over the years, man has selected and cultivated the non-explosive grains, attempting to develop larger seeds. This has resulted in today’s wheat, barley, corn and rice (compare them to the less-cultivated amaranth, for example, or even smaller species.)

Within this important family, there is a “Jewish” sub-family, the one termed “the five species of grain.” These are the grains belonging to the “wheat tribe” (the Poaidae sub-family), characterized by their ability to leaven and swell. This is generated by gluten, a general term for some of the proteins typical in the various species of grain. Gluten is distinctive in its being insoluble. The origin of the word “gluten” is from gluttire, meaning ‘to swallow,’ because gluten changes its spatial structure when water is added and the dough is kneaded, so the dough receives mechanical strength and can hoard gas (created by yeast and enzymes). In the process of kneading, the gluten is developed, creating a three-dimensional structure of a net of thin elastic filaments that act to “trap” and “withhold” the gases and water vapors formed within the dough-hollow during the rising and subsequent baking. (Further details on gluten can be found here)

This group has special laws in Judaism, which include, aside from Pesach issues, the blessing of Hamotsi before eating, reciting the Birkat HaMazon afterwards, and the mitzvah of “taking Challah.”

The four species of grain we use for daily consumption that belong to the gluten wheat tribe are (right to left): wheat, barley, rye and spelt. Four? But what is the fifth? What about the oats? Well, here is the big surprise: Oats do not contain gluten, nor do they leaven or swell. Professor Yehuda Felix has identified the oats of “the five species of grain” with a species of barley. He argues that it is impossible that oat is in oatmeal, since oatmeal does not contain gluten and was not known to our sages during the Talmud and Mishna. However, here we encounter a different obstacle, not botanical but much more complicated, called the “modification of Jewish custom,” which I will relate to soon.

Our second family, the legumes (Fabaceae), is a very dear one to farmers. I will not extol itsvirtues here, but that will surely come in a future newsletter. For now, let me simply note that there is no botanical similarity between legumes and the Graminaes. When we discuss legumes on Pesach, we don’t really mean the legume family, but rather the Pesach Askenazi “small legumes,” a varied and strange group composed of rice, millet and corn (Gramineae family) as well as beans, hummus, fenugreek, soy, lentils, fava beans, white beans, Tamarindus Indica (Fabaceae family), sunflower seeds, mustard, buckwheat, kummel and sesame (Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Polygonaceae, Apiaceae, Pedaliaceae families). In short, the prohibition of kitniyot on Pesach includes an assortment of all kinds of botanical grains and seeds.

And why is this? Traditionally, the prohibition dates back to a European Jewish custom over 700 years old, but its reasons are not crystal clear. The gist of a Google search shows three main reasons, none of which derives from a direct Divine prohibition, but rather from doubts and misgivings:

* In Ashkenazi communities, kitniyot were used in cooking, and the Rabbis did not trust the cooks’ ability to differentiate between rice and groats.

* As there are various kitniyot that can produce flour, the Rabbis worried that some Jews would allow themselves the use of chametz flour as well. Although in ancient periods the Rabbis were not concerned because the custom was very clear, the exile of the Jews caused sages to fear that lack of knowledge could lead to mistakes.

* The physical resemblance between grains and kitniyot: In both cases, these are grains stored in silos for relatively long periods of time, causing some concern that the kosher kitniyot would mix with wheat and barley seeds, which would inevitably lead to cooking chametz on Pesach. The wagons leading the kitniot to market were also used to transport grains, which might result in blending.

* And if I may add, growing in the fields could to be related as well. Over the early Middle Ages, farmers in Europe transferred to a tri-annual crop rotation: one year they planted grains, the next- legumes and the third year the field was left fallow. This method must have created “volunteer” growth of some grains in the legume field, which might have entered the kitniyot sacks.

In light of these fears, the Rabbis decided that Ashkenazim should be ‘better safe than sorry’ (I’m sure this sounds better in Yiddish), and prohibited legumes and other grains, seeds, kernels, granules and whatnot from the Pesach fare.

I wish you all a nice, smiley, cozy, spring-like Pesach, and once again invite you to visit us at our Open Day on Thursday, in our lovely, springtime farm. This year we actually have a sweet little thicket where we’ll be holding the festivities. It’ll be lots of fun!

Happy Pesach! Alon, Bat Ami and the Chubeza team

______________________________________________

This week in our spring box:

Monday: cucumbers, carrots, fennel, leeks, tomatoes, potatoes, celeriac, lettuce, red or green mustard greens, green onions, parsley root-small boxes only.

In the large box, in addition: Swiss chard, mini broccoli, dill, parsley

Wednesday:green cabbage or mini broccoli, parsley, tomatoes, celery or celeriac, Swiss chard, green onions, carrots, lettuce, mustard greens (Perfect for Maror…), potatoes, cucumbers

In the large box, in addition: dill/cilantro, fennel, leeks