Over the past few weeks, your boxes have proudly hosted the king of summer, his royal highness The Corn. Each year he accompanies us from June to December, joins us as we bid the schoolyear farewell, dives in the pool over summer vacation and goes back to school with us come fall. The corn crop begins to ripen in June, which this year was overly nice and spring-like, then faithfully moves at our side into the intolerable heat of July-August, takes a break in September (more about that soon), breathes a sigh of relief along with us in October, ascertains that the weather has regained its sanity, and only then bids us farewell in December. Now that’s what I call a king!

Corn is evidently one of the first crops the Americans learned to grow some 7,000 years ago, gleaners (most probably Mayan women, or women of a neighboring tribe in Central America) noticed a spontaneous mutant among the weeds, a teosinte, with a cob that was longer and filled with seeds larger than in your average ancient weed. Something sparked their intuition, and they tasted it – to their great delight. They also discovered that seeds which fell to the ground sprouted to become a mature plant that yielded more cobs. After some time, they learned that if they kept and seeded the better seed varieties, the next crop would be even greater improved! Thus, in the process of selecting the optimal plants to grow and harvest from year to year, the “cultured corn” developed sporting large, juicy kernels securely attached to the cob. Today, corn is one of the few plants which cannot reproduce without human aid, since the separate seeds must be sown in order for the plant to germinate.

To your left is the ancient corn, and to your right is today’s cultured variety:

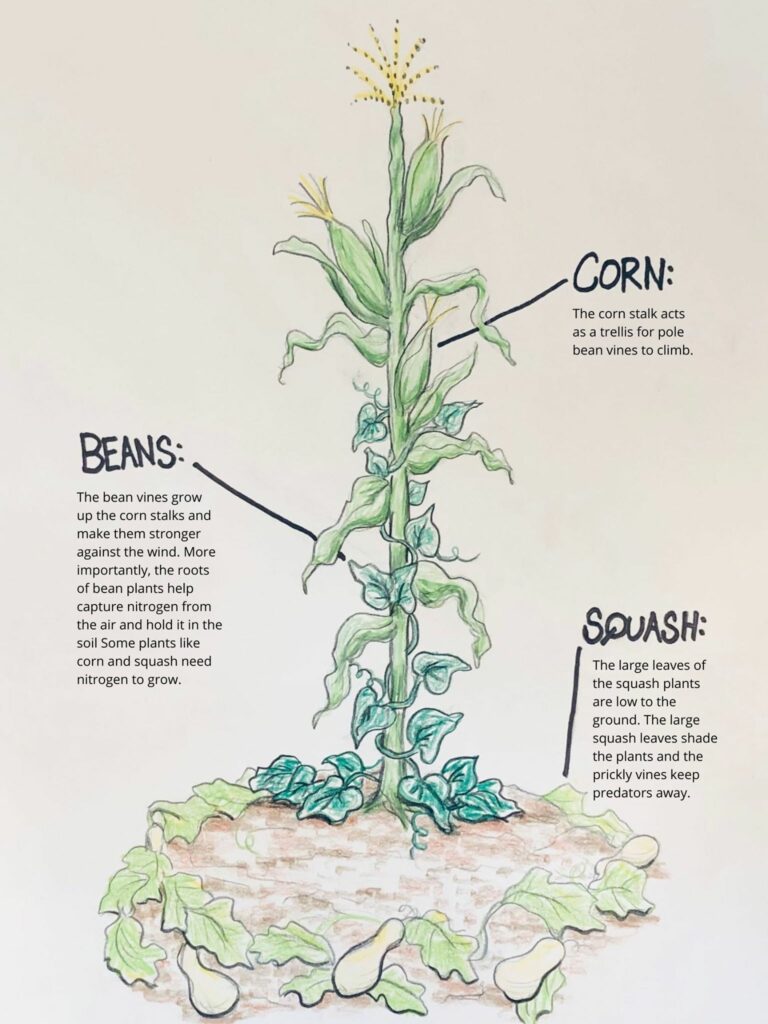

At the next stage, American farmers discovered that if they grow corn, beans and squash, they could actually make a decent basic diet out of them. The plants also grew well together: the corn acted as a supporting pole for the bean to climb upon, and the squash grew on the earth as live mulch, preventing weeds and sealing in the moisture.

This threesome, which earned the title “the three sisters,” is an excellent example of the plant guild/community: a group of plants which become valuable when they grow together. The key to their success is the positive reciprocal relationship amongst them: each plant contributes to its neighbors, and receives from the neighbors in return. And just like human communities, a good plant guild is a more independent entity, stronger, healthier and easier to maintain than growing plants which are not connected to one another. This agricultural development proved to be so time-efficient that it gave the growers enough spare moments to build houses, weave rugs and baskets, develop astronomy and math, and of course – to party…

Native Americans used corn in a variety of ways. They ate it fresh or cooked, dried the cob and ground it into flour, ground the fresh kernels to make the moist corn porridge Polenta, decorated their homes with colorful corn, popped the kernels for popcorn, fed the cobs to animals, and more. Each part of the corn plant had its advantages and uses. The corn stalks’ height enabled trellising beanstalks, the corn stem poles were used for building, fishing and more, and the corn silk to treat kidney ailments and to weave mats, baskets, crafted masks, moccasins and corncob dolls:

Over the years, many changes occurred in the cultivation and uses of corn – once so substantial in the lives of native Americans – transforming it to an industrialized product, engineered and empty.

Today, too, we are dependent upon corn in every realm, especially food: Almost every processed food contains corn, but corn of a very limited genetically-engineered variety that appears in its processed, worn and abused form, totally bereft of nutritional value, and of course, a product which demands an excessive exertion of energy.

We use cornstarch for thickening and gluing, and corn syrup for sweetening. Expansion materials, emulsifiers, food coloring, and citric acid are all derived from corn, as is most of the animal fodder in the meat industry. Corn also serves a role in the production of plastic and oil. (If you wish to learn more about corn and food in our world, I highly recommend Michael Pollan’s book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma.)

And yet, it will forever promise the sheer joy of sinking one’s teeth into a fresh ear of corn. At Chubeza, we begin seeding corn at the end of March. The first two seeding rounds are around one month apart. A short two-three weeks later it’s time for the next round of seeding, and two weeks later another round. Then begins a weekly seeding schedule. The reason for this fluctuation is the change in seasons and the rising summer temperatures. If the first round needed between 100-110 days to reach ripeness, the last rounds ripen within 80-90 days. Thus, these intervals between seeding rounds enable us to distribute sweet, juicy ears of corn in your boxes almost every week.

Each seeding, we insert two beds (4 rows) of yellowish, hard, wrinkled seeds into the earth. When I say we “insert” them, I mean it, because after many attempts to sow the corn with a seeder, we realized that nothing beats doing it by hand. We notch furrows in the earth and scatter the seeds at around 10-15 cm apart. Afterwards, we cover the furrow, water the earth, and pray fervently for healthy, abundant growth.

After the initial sprouting, the corn grows rapidly, producing beds of tall, strong, erect stalks which you can actually get lost in. A group of young visitors to Chubeza decided to check how it feels to enter the corn bed jungle:

Since we seed the corn repeatedly at relatively short intervals, a tour of the field reveals corn beds of varying heights, from 20 cm munchkins, through 50, 80 and 150 cm tall guys, all the way to towering stalks of 2 meters and more! Meanwhile, the plants that have already been harvested and are now retired have pulled out of the race, pay no attention to the people, and blissfully yellow away in the summer sun. (I like them the most…)

Since Chubeza’s first year, we have continuously sown corn during the summer, and every year we (and you as well) have suffered frequent visits from corn-borer worms, primarily in the late summer months. And since corn is one of our most looked-forward-to veggies, the disappointment in discovering that the worms beat us to it and gnawed through the cob is incredibly annoying. Thus, this year we decided to take a break from sowing corn at the very time when the corn growth is at its zenith. As such, we can prevent the eager corn-borer worm from multiplying and partying at the expense of our sweet, yummy ears of corn, and we’ll resume seeding again as the worms kindly decrease their seasonal pastime. After three consecutive months of corn seeding, we took a break at the end of June, and will resume sowing in mid-August. Due to the delayed arrival of cold weather over recent years (winter keeps arriving later and later), this year we will also extend the seeding by several weeks, hoping to harvest corn by December.

Apart from the nasty corn-borers, other partners have also discovered the wondrous Chubeza corn: wild animals in the area have converged on our cornfields (probably as the rumor of delicious corn went viral), devouring and destroying from row to row as they consumed hundreds of corn cobs! This was not the first time that wild animals, probably wild boars and jackals, have wreaked havoc in our corn beds. In recent years we have been confronting the problem by fencing off the plot with an electric fence that deters the scavengers from entering and destroying our corn. We stretch three electric wires on three metal poles around the plot. At night, we switch on the electricity. If a nibbler tries to encroach, s/he receives a short shock that promptly changes their dinner plans. The wires are stretched rather low, at nose-height of these four-legged creatures, enabling us to smoothly step over them. Here, this is what this looks like:

Chubeza’s corn varieties belong to the “super-sweet” variety (SH2). True to its name, this corn is indeed super and sweet. And all thanks to a mutation! To set your mind at ease, this is not genetic engineering, but rather a mutation that happened naturally in the field, outside the laboratory walls, and was later developed by normal hybridization, like other caged seeds. Most of the corn seeded in the world is not even sweet (field/dent corn), but is produced primarily for animal fodder, for cornflower production, and for such industrial uses as ethanol for fuel, for the plastic industry, for corn oil and various other additives. This field corn is actually the ancient corn variety that was grown in Central and South America thousands of years ago.

A unique feature of corn, which is also a great advantage, is that it is unstable. Corn is a crop that is sensitive to mutations and changes (occurring in nature) to its genetic structure, thus resulting in a wide, sweeping genetic diversity of corn varieties in different colors, different shapes and different levels of sweetness. Corn holds a place of honor in scientific research where the corn plant has helped lead to some of the most important discoveries in genetics, such as that of transposons.

Sweet corn has been known to Western culture from 1770. It is not clear when this (natural) mutation that led to its creation first occurred, but it caused a double amount of sugar to be stored in the storage tissue (endosperm) of the seed-kernel. There are hundreds of sweet corn varieties in this group, including the fresh corn (on the cob) that is common here in Israel. Yet the sweetness of corn is living on borrowed time. Corn is a grain that from the moment it ripens, and particularly from the moment it is picked from the plant, the process of turning the sugars into starch begins within. In this process, the corn loses its sweetness and becomes mealy and starchy, thus corn that has been harvested for several days will have already lost much of its sweetness.

In recent years, two other groups of sweet corn varieties have been developed, both based on genetic mutations that occurred naturally in corn, which were then carefully developed to create stable varieties for agricultural use. One is the “sugar enhanced” (SE) corn, boasting higher sugar content than traditional sweet corn, which is why, when refrigerated, it retains sweetness 2-4 days after harvest. The second group is the Super-Sweet corn (SH2), three times sweeter than the other varieties. And most important here, the process of the sugar transforming to starch is far slower, allowing it to remain sweet up to ten days after harvest (when refrigerated). This, of course, has many advantages, specifically for export to distant markets—but we can enjoy these lovable mutants very close to when the corn was picked: triply sweet and fresh.

This year we are also growing white corn, another variety of sweet corn, but you probably won’t be treated to tasting totally white corn. If you come across cobs with white kernels, they will be bi-colored, with white and yellow kernels together… Why? We actually planted white corn, but several beds away was yellow corn. Since corn is pollinated by the wind, some of the pollen from the yellow corn reached the ovaries of the white corn flowers, transforming various kernels to yellow.

Wishing everyone a sweet, colorful, transforming week,

Alon, Bat-Ami, Dror, Orin, and the entire Chubeza team

_________________________________________________

WHAT’S IN THIS WEEK’S BOXES?

Monday: Japanese Amoro pumpkin/spaghetti squash/butternut squash/acorn squash, lettuce, squash+zucchini, eggplant/beets/fakus, cherry tomatoes/green or yellow beans, potatoes, basil/coriander, corn, tomatoes, cucumbers, lettuce, melon/watermelon. SPECIAL GIFT FOR ALL: New Zealand spinach/Swiss chard.

Large box, in addition: Red bell peppers/slice of pumpkin, leeks/onions, parsley.

FRUIT BOXES: Bananas, grapes, nectarines. Large box: All of the above + mango/yellow plums.

Wednesday: Japanese Amoro pumpkin/spaghetti squash/butternut squash/acorn squash, squash+zucchini, eggplant/slice of pumpkin, cherry tomatoes/green or yellow beans, potatoes, basil/coriander, corn, tomatoes, cucumbers, melon/watermelon. SPECIAL GIFT FOR ALL: New Zealand spinach/Swiss chard.

Large box, in addition: Red bell peppers/beets/fakus, leeks/onions, parsley.

FRUIT BOXES: Ana apples, grapes, nectarines. Large box: All of the above + mango.